Following in the Footsteps of Native Americans Gives Perspective On What Being American Means

From the Palouse to the Channeled Scablands, Learning the History of Native Peoples of the Inland Northwest can be Eye Opening

In 1996, my mother took me on a hundred-mile horseback ride through the Hells Canyon of Southeast Washington, Western Idaho, and Eastern Oregon.

We set off from Lewiston, Idaho with a group of about 50 riders to retrace part of the journey Chief Joseph and his Wallowa band of the Nez Perce and their Palouse allies embarked on in 1877. It’s a military action that has gone down in history books as the Nez Perce War, but calling it that is stretching the truth. It was a bloody chase.

By the end, the natives, many of whom were women and children, had traveled 1,170 miles across what is now Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana in a fighting retreat that earned them respect and even admiration for their bravery and dignity in the face of the best of what the US military could throw at them.

With only about 200 fighting men, Chief Joseph led his force against roughly 2000 soldiers in eighteen engagements, including four major battles and at least four fiercely contested skirmishes.

The war earned Chief Joesph the nickname “The Red Napoleon” in the press. The Montana newspaper New North-West stated: "Their warfare since they entered Montana has been almost universally marked so far by the highest characteristics recognized by civilized nations.”

The Nez Perce were “non-treaty Indians,” which means they had no agreement with the US government for settling on reservations. Other tribes were given land, fishing and grazing rights, and more as part of their agreement to settle on reservations. This was not the case for the “non-treaty” tribes. So their goal was to join Chief Sitting Bull and his Lakota in Canada, out of reach of the US government.

But rather than let them cross into Canada and join the feared war chief responsible for the defeat of General George Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn, the US decided they couldn’t let that happen.

After an exhausting slog, US forces launched an early morning raid against the Nex Perce encampment 40 miles south of the Canadian border. Yet even this wasn’t enough to make Chief Joseph and his men capitulate. After a stalemate that lasted three days, US forces were reinforced and Chief Joseph surrendered, making his famous “I Will Fight No More Forever” speech.

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our Chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. The old men are all killed. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead,” he said.

As I, on my Appaloosa pony, followed behind my mother crossing and recrossing the Snake River, riding on switchbacked trails up the walls and over the peaks of Hells Canyon, I couldn’t help but think what it must have been like for the Nez Perce and their allies. It was the most grueling ride of my life. It nearly killed my horse. And we only retraced 100 miles of the nearly 1,200 Chief Joseph and his followers traveled.

I hated every minute of it. I’m sure they did too. But I got a shower most nights and a hot meal every night, and after a week I could go home to my soft bed. Chief Joseph and his followers were being shot at and attacked the entire way. And after their trip was over they were put on reservations – forced to live as captives on a fraction of their own ancestral lands.

I started remembering that experience recently as I was on another ride focused on Native American history in our region. This time I was riding on a bus and not a horse (putting me a man of my Rubenesque girth on a pony these days would constitute animal cruelty).

The focus of this trip was the sacred sites of the Wenatchi and Moses-Columbia tribes. It was organized by the Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center and led by Randy Lewis, an elder of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Lewis has dedicated his life to telling the stories of his people and educating folks on the history of the Wenatchi, Moses-Columbia and other tribes that make up the Colville Confederation.

Lewis is an oral historian, and when you’re listening to him it’s not hard to understand the captivating power of the oral tradition the Wenatchi and other native peoples used to hand down their history from one generation to the next.

It’s part history and mythology class, part natural science and horticulture lesson, and part stand-up gig. As we traveled from Wenatchee past Rock Island, up Moses Coulee to Dry Fall, and then on to Steamboat Rock and Grand Coulee, Lewis would point at important rock formations and other natural landmarks and explain their significance.

He told the story of the signing rocks of Moses Coulee, which absorbed the spirits of the people and talked about how you can still hear their voices in the rocks if you listen hard enough.

He talked about the islands near the Rock Island dam, which are part of an ancient dragon Spexman. The dragon was defeated by Red Star and Blue Star, important mythical twins to the Wenatchi tribe, and they distributed his body parts across the Wenatchee Valley.

The islands of the rock island rapids are now mostly underwater, but before they were submerged by the waters of the Columbia after the Rock Island Dam was built in 1933 they were home to some of the most well-preserved petroglyphs in the US.

Lewis told stories about Coyote, an important god to the Wenatchi tribe, who is known as a protector and provider as well as a devourer of human wives and a sexual deviant.

“That’s Coyote’s penis,” Lewis said, pointing to a basalt column in the Moses Coulee, “his wife pulled a Lorena Bobbitt, cut it off, and threw it across the Coulee.”

The surprisingly graphic tidbit coming out of left field had me grinning ear-to-ear, but the mostly older crowd of about 30 folks from Wenatchee didn’t know exactly how to react and there was silence on the bus.

Not long after that Lewis called for the driver to stop, and we got off and watched him dig up roots that represented a staple of the native diet. He passed his root-digging stick around for others to try and we stood in the spring sun and ate the slightly bitter, chalky roots before piling back on the bus and traveling on to Steamboat Rock.

Steamboat Rock is a sacred site to the native people of the region, Lewis said, and on top is where Coyote placed all the best flora and fauna. He did this to keep it out of reach from the people because a chief refused Coyote his daughter’s hand in marriage.

While the people may have suffered because of the chief’s decision, Lewis said it was lucky for the Chief’s daughter because Coyote had a habit of eating his wives.

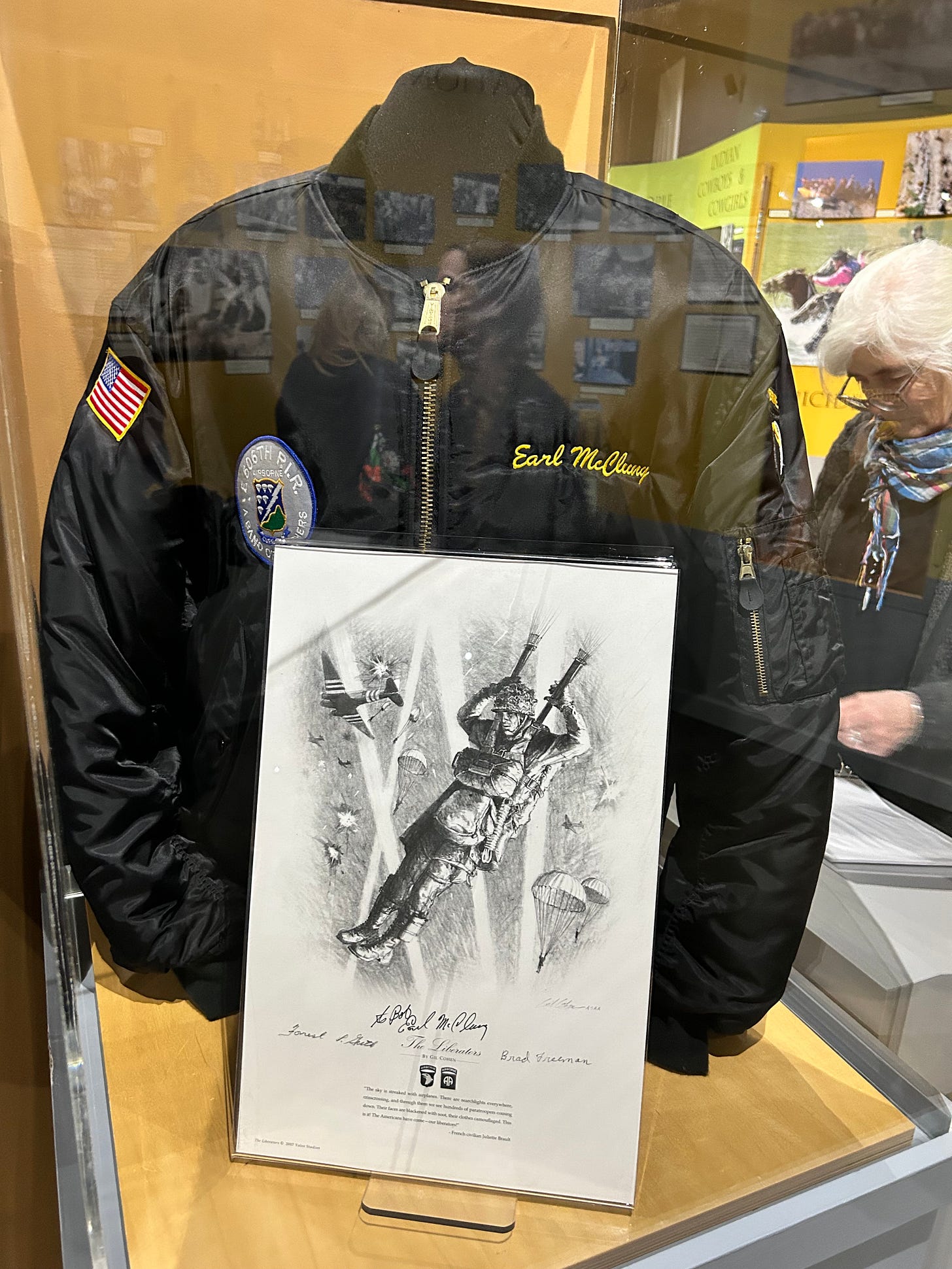

In Grand Coulee, we visited the Colville Tribal Museum and I learned about an American war hero Sergeant Earl “One Lung” McClung.

McClung was a Colville Tribal member born to the Lakes band and in World War II he joined the famous 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment with the 101st Airborne Division, also known as Easy Company. Stephen Ambrose’s book and HBO series, both titled “Band of Brothers,” are about Easy Company and they made the unit internationally famous.

McClung’s Easy Company jacket is in a glass case in the museum and the patch on it caught my eye. Being a huge history nerd, I have read Ambrose’s book and watched the series multiple times. I even have a framed picture of Easy Company jumping over Normandy signed by “Wild Bill” Guarnere, one of the most famous Easy Company soldiers.

So you can imagine my shock and delight as I read McClung’s story on the placard next to the glass case.

“McClung made his first combat jump into Normandy on the night before D-Day,” it read. “He landed in the town square of Ste. Mere Eglise. McClung always carried his M1 rifle in his hands while jumping. This habit saved his life; he was able to return fire during the jump, killing two Germans.”

It’s a scene straight out of a movie, and it would have made an amazing sequence in the HBO series produced by Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg, yet I’d never heard of it, or McClung.

As we filed out of the museum and prepared to get back on the bus, I remarked about the fact that the Colville reservation has its own bonafide “Band of Brothers” war hero to my friend Mary Big-Bull Lewis, Randy’s niece.

I wondered aloud why any Native American would volunteer to fight for the US government, after the way our county hounded and killed the indigenous people of this continent from coast to coast, eradicating those they could and shuffling the rest onto reservations.

“Because this land was their land before the United States was ever here,” she said. “He was defending his land.”

And that makes sense. If the Axis powers would have emerged victorious in World War II, there’s no doubt the Germans and Japanese would have carved up North America and imposed their will over everyone here, Native Americans included. In fact, you could argue that the indigenous peoples of North America would have suffered a worse fate than the white Anglo-Saxon protestant inhabitants of the continent if the Nazis and their allies had won. In fact, they probably would have been treated as badly as the Roma and the Jews.

I was expecting to just learn about rocks, plants, and the mythology of our region's tribes. Instead, I was reminded that these people didn’t disappear from this landscape. They still inhabit it. They never left.

Through the stories told by people like Randy Lewis, their histories are kept alive. The bravery and sacrifice of men like Earl McClung prove that they are just as American as any corn-fed Midwesterner, New England Yankee, or Southern boy. They have as much ownership over the title “American” as anyone else.

In fact, maybe they have more of a claim to that title than we “newcomers” do.

If you’d like to read more about this trip and learn more about Randy Lewis and his tours through the Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center, Crosscut will be publishing an article I wrote about it this coming week.

Archeologist Praises Rock Island Symbols

Reprint from an article in the Wenatchee Daily World, April 1926.

The Great Northern Semaphore for April contains the following article written by C.H. Robinson, archeologist of Normal, Illinois:

“Last fall the writer, in company with Adam East secretary, Chelan County Archaeological Society, made a reconnaissance of the beautiful Columbia River district not far from the junction of the Wenatchee River, at a point known locally as the Rock Island Rapids. Here the Columbia River is thrown into whirlpool action due to the basaltic columnar lava beds. The river is approximately three-fourths mile in width at this point, with a number of small, and one large, Memalocse or burial islands.

The large island is surrounded by such turbulent water that few white men have ever had the nerve to land upon it. Owing to the undertow. It is positively dangerous to attempt to use an ordinary row boat. It is assumed that the long cedar canoes used by our skillful aboriginal Americans were built of such length as to reach from the crest to crest of this seething boiling, whirlpool action of the Columbia River at the Island. No doubt generation after generation reached this Memaloose island in safety on their sad and sacred mission to bury their dead, and record their story on the rock of ages somewhat as we do in a modern cemetery.

These missions were carried on covering a period of time recorded in hundreds and perhaps thousands of years, mute evidence of which has been indelibly inscribed upon the rocks, which now present the largest and most interesting array of petroglyphs to be found anywhere in this section of the great northwest country. This vast stone library depicts in symbolic form, thousands of years of deeply pecked records, clear cut upon the hard columnar basalt surface of this “Giants Causeway” of the Columbia. The rocks, rising almost perpendicular out of this turbulent stream, are literally covered with petroglyphs awaiting translation by some eminent body or college which can spend the amount of time this place deserves.

At some little risk to the writer, through the aid of Mr. East, secured the photographs illustrating this article, which give the reader some idea of the character and extent of this archeological wonderland.

In the vicinity of the Rock Island Rapids has been found much evidence of aboriginal life and customs, not only in the nature of the petroglyphs and skeletal remains, but large numbers of stone artifacts indicating a succession of natural changes from early stone age to first contact with white men. Characteristic evidence of this may be seen in the large and valuable private collection of Adam East, of Wenatchee, Washington.

Recently it was the pleasure of the writer to look over Mr. East’s most complete and systemic collection in the nature of several thousands objects, such as stone artifacts, ornaments and problematical stones, wrought from a large material, such as lava, granite, slate, obsidian, hematite, chalcedony, and agate, together with stone, shell, copper, iron and catlinite. All go to make up such a bewildering and scientific collection which would require much time to properly classify.

It was gratifying to learn that a movement is now on foot, through the efforts of the Wenatchee Archaeological Society to safeguard Rock Island as a state or government reserve. A cableway may be constructed between the mainland and Memaloose Island. Every effort will be made to prevent any further vandalism among these records of the past.”

I reached out to Randy Lewis to get some more information about the Rock Island rapid islands and their meaning to the Wenatchi and Moses-Columbia.

A version of this article was originally published on Friday, May 5, 2023, as my column for Source ONE News.

I too fought in combat (Vietnam) w/a Native American in my rifle squad (I was the actual). He was a very proud outstanding US Marine rifleman, following in his family's tradition; fighting for his (not our) native land. I was proud to serve with him. Excellent piece Dom (as usual).

I love hearing this rich history. My grandsons enjoyed to Spexman tale and we continue to point out the rock formations we've learned about from the book.