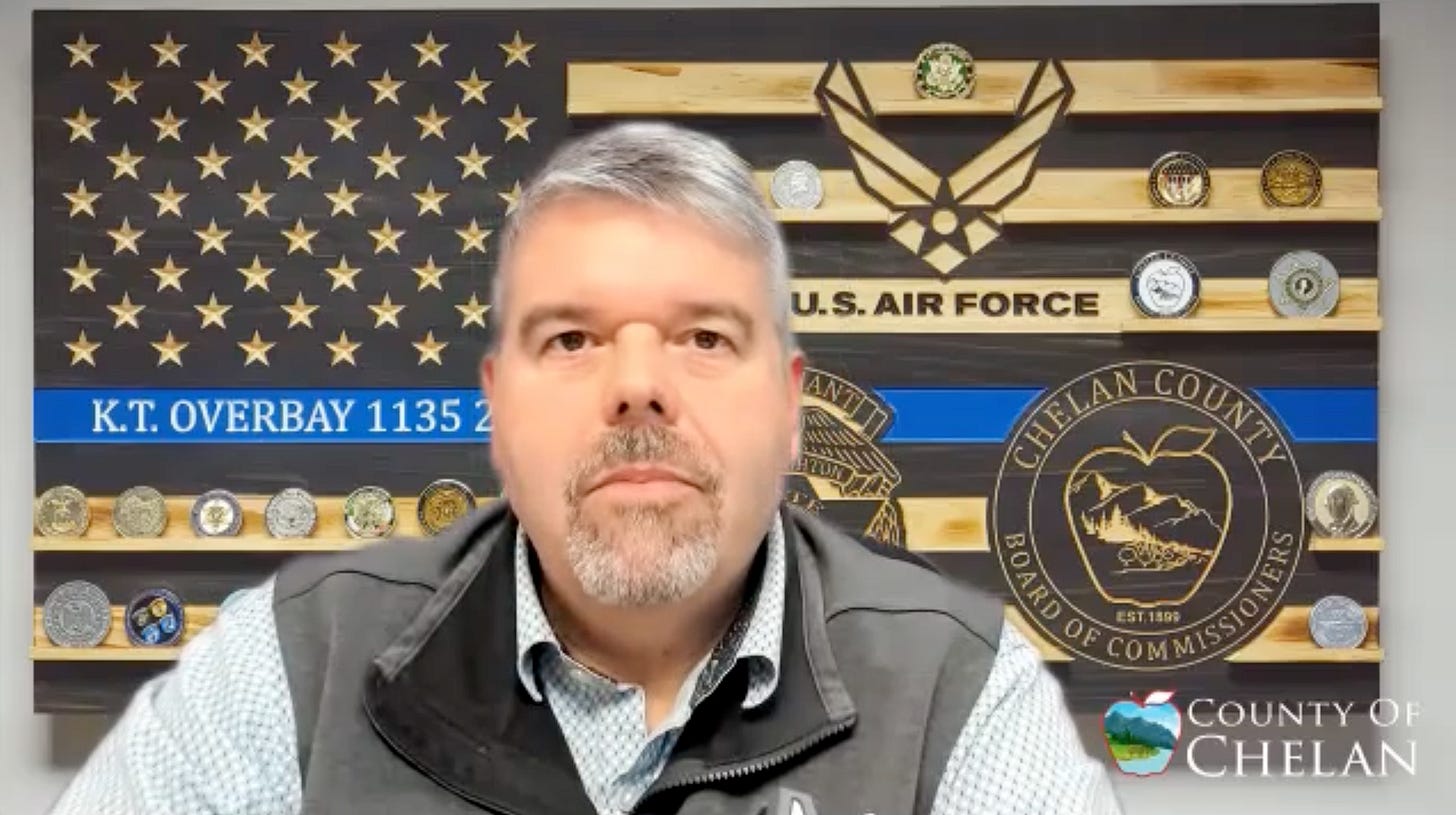

"He Runs The County Like A Dictator:" Former Chelan County Commissioner Speaks Out About Kevin Overbay

She and others describe Overbay as manipulative, vindictive and unethical; outline habitual violations of state's public meetings law as well as nepotism, cronyism and more

Note: This is part II of a two-part series on Chelan County government. To read Part I, click here.

Chelan County Commissioner Kevin Overbay runs the county like it’s his kingdom and in many ways the county’s problems – from the $4.1 budget deficit to the public’s frustration with a dysfunctional County Development Department – can be traced back to him, says former Chelan County Commissioner Tiffany Gering.

Gering, a Republican, said she didn’t run for a second term because of Overbay.

“Kevin has no integrity,” Gering said. “You do not want your electeds – the people that represent you – to not have integrity.”

The way she sees it, Overbay isn’t a Republican at all. He has sacrificed Republican principles in order to grow a county government that is in many ways bloated and wasteful of taxpayer dollars, she said.

“Because he is creating his kingdom,” Gering said. “And that’s why I would say he’s not a Republican. He is growing government like you would not believe, he wants all the pots of money.”

She and former subordinates, all females, describe Overbay as an overbearing, manipulative, vindictive, condescending, self-serving, narcissistic, misogynistic micromanager. They say he regularly violates the Open Public Meetings Act, which he treats with contempt.

The OPMA is a Washington state law that “requires that all meetings of governing bodies of public agencies, including cities, counties, and special purpose districts, be open to the public,” according to the website.

If elected representatives are discussing business and have formed a quorum, that is a public meeting, whether that be in person, on the phone or even in a group chat. Since Chelan County has just three commissioners, if two of them get together for coffee, that’s a quorum and if they talk county business, that’s technically a public meeting.

Gering and Sasha Sleiman, the county’s former Housing Programs Manager, and other sources who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of reprisal from Overbay, say the statute is violated habitually and no one is ever held accountable for violating that law.

“With the OPMA violations there’s no accountability for commissioners. None,” Gering said. “Because when staff tries to hold the commissioners accountable Kevin has made comments like, ‘I’ll just pay the fine.’”

For Overbay and other commissioners to be held accountable, a staff member would have to lodge a complaint with the state Attorney General’s Office, Gering said. Their name would be on the paperwork, which is public record. So county employees are naturally concerned about the consequences of alerting the AG’s office.

Gering said Overbay runs the county not as a co-equal member of a board of three – but as the county’s boss.

“He runs the county like a dictator,” she said. “He is making decisions for the board without our knowledge all the time.”

He manages department heads as if they work for him alone and makes political promises to individual citizens at the expense of what is for the good of the greatest number of county citizens, Gering said.

And he brags about his dominance.

“He tells everyone, ‘I'm always ten steps ahead.’ Which is very true,” she said. “Because what he’s done is gone out and politicked and oftentimes talked to another commissioner. Which is illegal – a violation of OPMA.”

He’s so blatant about it because he thinks he’s untouchable, she said. And if you cross him you better watch out.

“If you disagree with him, you are the enemy,” Gering said. “You need to prepare to go to battle. And it doesn’t matter what the topic is.”

Morgan Damerow, Assistant Attorney General for Open Government with the state AG’s office in Olympia, said superior courts are responsible for enforcing OPMA violations and provided an example of what repeated violations of the act could bring for elected officials.

They also wrote that it’s not just county employees who can make a complaint about OPMA violations.

“For example, if an individual believes they have evidence to establish a governing body did not satisfy the OPMA’s notice and open meeting requirements, that individual can file an action in the superior courts under RCW 42.30.120. Should a court agree an OPMA violation occurred, the court can impose a five hundred dollar penalty for the first knowing violation, and a penalty of one thousand dollars for each subsequent knowing violation, against each member of the governing body attending the meeting. RCW 42.30.120,” Damerow wrote in an email. “Any person who prevails against a public agency in any action in the courts for a violation of chapter 42.30 RCW shall be awarded all costs, including reasonable attorneys' fees, incurred in connection with such legal action. Id. In addition to penalties, a court could nullify any action taken in violation of the OPMA. A suit could also seek an injunction or mandamus for the purpose of preventing OPMA violations.”

Damerow wrote that there’s one other thing to be aware of concerning OPMA violations.

“An elected officials failure to comply with the OPMA may form the basis for a recall petition against the elected official.”

Those who have the most evidence of OPMA violations are, of course, Overbay’s peers and subordinates. But his wrath is something everyone in Chelan County government know to steer clear of.

It’s not just about avoiding his ire though, those in his orbit must also be pliant.

“If Kevin cannot control someone and he knows that, if you’re staff or peers, you have a target on your back,” Gering said. “And I have seen that time and time again with staff at the county.”

When it comes to his peers, i.e. the other two county commissioners, Gering said he bullied former Commissioner Bob Bugert and does the same to the man who took his place – Shon Smith.

Gering found herself on Overbay’s bad side about six months into her term. She said that right away she had been pressured to vote along with her fellow board members because she was told they liked to “pass things unanimously.”

“A chain of events had happened in those first six months when I realized, ‘Oh, he wanted me in office because he thought he could control me,’” Gering said.